It’s Monday again, the start of a new work week. I guess this must be the 4th week of the year, since Saturday was January 21st, and 21 is 3 times 7, and this year and month started on a Sunday. I’m at the bus stop again, writing this on my phone again while waiting for the first bus. It’s generally better, for me at least, to wait somewhere to which I’ve already traveled, rather than waiting before I travel. That way I can just sit still until the next stage of my journey.

Unfortunately, this bus stop has a strong smell of human urine this morning. I don’t know if that’s because the weekend just passed, and people get drunk and pee in inappropriate places on the weekend sometimes, or if that homeless person spent more time here than expected and had to pee during that time. I’ve not noticed the smell before, so it doesn’t seem to be a frequent thing. I suppose if it had rained there would probably not be any residual odor, but it’s not the rainy part of the year down here in south Florida.

I had thought to myself, if the homeless person were to have been lying out at the bus stop again, I would go to the other nearby stop that I had (internally) recommended to her a few days ago. That’s where I usually get off the bus at the end of the day, so it wouldn’t be a strange one for me to use.

It is curious‒I don’t know if other people do this or notice it or what have you, but I often take slightly different routes when going to and from a place. Some of that is probably just a byproduct of perception, in that certain paths look or seem easier from one angle compared to another. They can even be easier to see from one direction compared to another.

Sometimes it’s a matter of lighting and timing, such as the fact that, on my way back to the train after work, I take a slightly parallel portion of the route (which in the morning just goes on down the main road) because there’s a nice, quieter, tree-lined block behind the regional courthouse, and in the evening, when there’s light and I’m done with the work day, it’s more pleasant to walk there. It also goes directly to the side of the tracks where I catch the train in the evening, whereas when I’m getting off the train, it would require a significant detour.

All this is trivia, but my point is that having these different routes when going one direction compared to another seems to be ubiquitous, at least for me, and I suspect I’m not alone in this. This means, of course, that the routes become a kind of circle, rather than simply a reversible, oscillating process.

Of course no macroscopic processes of that sort are actually reversible, anyway, because of friction and the creation of increasing entropy, but even if one could eliminate such things, a to-and-from trip that takes different routes could have a net gain or loss*‒I think loss would be most likely‒and this loss could be perpetual and steady.

It’s a bit like that economics or game theory or decision theory idea whereby if someone prefers place A to place B, and prefers place B to place C, but prefers place C to place A, one could effectively be induced to pay to go in an endless cycle, from A to C to B to A to C to B, etc. Of course, it would be profoundly irrational for someone to do such a thing, but people get caught in even stupider cycles all the time, which are even more costly, but because they rarely pay attention to the nature of their actions as if from the outside, they often don’t even realize they’re doing something thoroughly irrational.

I return again to my musings on the myth of Sisyphus‒the actual myth, not the book by Camus, though I still haven’t answered his main question to my own satisfaction‒and how horrifying it is that Sisyphus is the one doing his own punishing.

Say what you will about the horrors of Prometheus’s fate, at least he was the passive, chained victim of it**. That may not make it better, and it may indeed be worse, but it is different. Sisyphus’s very mind has been changed, so that he feels an irresistible urge, or drive, to push his boulder, despite the fact that he never gets it to the top of the hill (or mountain or whatever) without it rolling back down again.

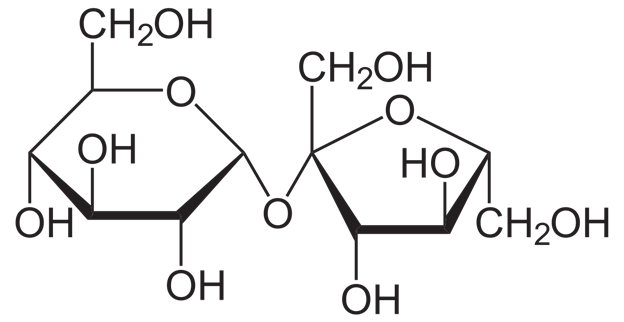

But, of course, we all do very similar things all the time. We eat to stay alive, and that eating gives us some pleasure, but the pleasure is transitory (as it must be) so soon we feel the urge to seek food again, and continue the cycle, which just spirals its way from bassinet to coffin, with the only certain outcome being that entropy in the universe will have been increased as part of the process.

Of course, the very universe itself may well be Sisyphean in nature‒see for instance my musing on Conformal Cyclic Cosmology, though even Inflationary cosmology can produce endless recurrences and infinite repetition. Heck, even the old-school Boltzmann type of heat death of a universe implicitly produced endless cycles as, eventually, entropy would occasionally dip low enough to regenerate all the “stuff” in a universe, before making its way back up again.

And, of course, if the universe were “closed”, which it doesn’t seem to be, it could expand, collapse, “bounce”, reexpand, etc. And if some of the “braneworld” scenarios in M Theory are right, there’s a cycle of brane-universes smacking into one another, restarting the hot Big Bang conditions over and over as they do***.

I don’t know where I’m going with this discussion, but in a way, that demonstrates my point. I write my blog post every workday, for no particular reason, but because various confluent and complex drives in my nervous system lead me to do it. Lather, rinse, repeat as needed.

Except, it’s not really “needed” in any deep sense. It’s just an urge. Even life itself is just a habit. And it’s not always a good one, is it?

*Of course, one’s potential energy returning to it’s original point in a reversible system means that no net “work” has been done, no matter what path has been followed, but I’m leaving aside such idealized systems…though at the tiniest level they may be more accurate representations of reality than any more “realistic” macroscopic analogy.

**Who else thought of The Big Lewbowski when reading that line?

***This is the sort of “collision” to which the title of The Chasm and the Collision refers.