Hello and good morning. It’s Thursday, and I’m writing this post on my lapcom. I feel as though I ought write these posts only on the computer (not that smartphones are not computers, but cut me a little slack on this, please), and I would be more inclined to do so if Microsoft would stop making Aptos the default font!!!!!

If I could go back in time and change something, that’s one of the things I would be inclined to change. If I found that there was one person mainly responsible for this new font, well…I don’t know if I’d go all Terminator on them and kill that person’s mother before that person was born, or kill the person when that person was a child, but something needs to be done to erase the stain of this horrible font from existence.

Certainly, if I were given* absolute power over the world, from this moment forward, one of the petty things I would do (I would try to keep the petty things to a very bare minimum, trust me**) is to eliminate that font from any and all standard computer systems anywhere. I would probably allow for individuals to select the font if they really like it, but would not let them use it on anything but internal work between people who also like the font.

Also, I would probably mark people who chose the font freely for a visit from my secret police.

I’m kidding. I despise the very notion of thought crime, let alone aesthetic policing in private matters. This is even though some people’s quality of thought sometimes feels like a crime against nature. But, of course, there cannot actually be crimes against nature. Nature does not punish one for disobedience to its laws. It’s simply not possible to do anything but follow them.

That’s one reason why I truly despise headlines like “The new finding by Hubble that breaks physics!” and whatnot. Not only are they plainly clickbait, they are stupid clickbait. I don’t know for sure if it’s just the headline writer or the writer of whatever the attached article might be who makes the headline in specific instances, but in either case, when I see headlines like that, I think that whoever wrote it really, clearly doesn’t understand physics very well. Nor do they the nature of scientific discovery and advancement. Because of that, I am far less likely to read the attached article (or watch the video) or even click on its link.

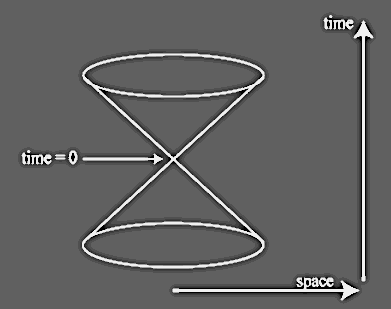

Nothing can break physics. If you find something that seems to violate physics as you understand it, what you have found is not a violation of physics but rather a place where your understanding of physics is clearly incorrect. This is far from a horrible thing. This is how progress in physics (and in other sciences) is made: by finding the places where our “understanding” doesn’t predict or describe what actually appears to be happening. The world cannot be “wrong”, so our understanding of it must be, and will need to be revised.

That’s progress.

One should be hesitant to give too much “trust” to anyone who refuses to change their mind. One of the best lines in a Doctor Who episode (not a truly great episode, maybe, but it has a wonderful speech by the Doctor) is after the Doctor has said to the “villain” (who goes by the human name Bonnie, though she is not human) “I just want you to think. Do you know what thinking is? It’s just a fancy word for changing your mind.”

Bonnie responds, “I will not change my mind.”

And the Doctor says, “Then you will die stupid.”***

This is simply true. If you never learn that you were wrong about something, if you never update your credences or think about things in a new way, you will never learn anything new or develop any better understanding of the world than you did when you formed those credences. Or, to paraphrase Eliezer Yudkowsky, if no state of the world can change the state of your retina and how you perceive that state, that’s called being blind.

I like to refer to Yudkowsky-sensei a lot, but that’s because he has said a lot of bright and interesting things, and he has said them well. It’s also nice to know that there are some highly intelligent and thoughtful people in the world—clearly there are, or humans would long since has gone the way of the trilobites—because the idiots and the assholes make so much noise.

The best evidence I see for the fact that most people are good or at least benign (overall) is that civilization still exists, and has done so for a long time. It is far easier to destroy than to create or even to maintain; the second law of thermodynamics tells us that things will fall apart even if we do nothing at all to break them (it says that more or less, anyway—that’s a bit of a bastardization of the proper, mathematical law, but it is related and implicit).

The fact that civilization still exists—so far, at least—seems to indicate that there must be a lot of people working to maintain and sustain and improve it, because we can easily see how much how many people seem to be trying to make it crumble****.

Assholes tend to make a lot of noise in the world, but they’re pretty much all full of shit and “hot air”. It’s worth it to keep this in mind, because there have always been plenty of such nether orifices out there, spewing their flatus everywhere like perverse crop-dusters. But the evidence strongly suggests that they are not the norm; they are just the noisiest.

I suppose that’s a good moral of sorts on which to end this post: Be willing, even eager, to change your mind when warranted, and try not to let the assholes make you think the world is no better than a camp latrine (even if you’re one of the assholes sometimes, which you are, since we all are, sometimes*****).

Though, to be fair, I am hardly the person to be giving that last piece of advice unironically.

TTFN

*If you must be given absolute power, do you actually then have absolute power? This is similar to the old song that says “Don’t ever take away our freedom.” If you have to beseech someone not to take away your freedom, you’re not free, and if you have to be given power, your power is clearly not absolute.

**Or don’t, if that’s not in your character. I’ve often spoken implicitly against the concept of trust, stating that I don’t feel that I can actually, truly trust any living person. It’s calculated risks all the way down, which is empirically true if nothing else. So, I can hardly scold someone if they don’t “trust” me. Go ahead, form your own conclusions. I do exhort you, though, to be as rational as possible when you form them, with your conclusions drawn as a consequence of the evidence and argument, not with your evidence and argument being curated based on your knee-jerk or at least hasty “conclusion”.

***He then proceeds to lay out the alternatives; he’s not making a threat, he’s making a point.

****When you read that, did you immediately think of your own least favorite political or other public figure, or perhaps of the people you encounter who disagree with your politics or religion or dietary preference or what have you? Be careful. Us/them thinking is not usually conducive to formulating true and accurate pictures of reality (though it did inspire at least one beautiful song):

*****We’re also all deuterostomes (I’m assuming only humans are reading this). Look it up. It’s kind of funny.