It’s Saturday, the 19th of November in 2022, and I’m going in to the office today, so I’m writing a blog post as well. I’m using my laptop to do it, and that’s nice—it lets me write a bit faster and with less pain at the base of my right thumb, which has some degenerative joint disease, mainly from years of writing a lot using pen and paper.

The other day I started responding to StephenB’s question about the next big medical cure I might expect, and he offered the three examples of cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. I addressed cancer—more or less—in that first blog post, which ended up being very long. So, today I’d like to at least start addressing the latter two diseases.

I’ll group them together because they are both diseases of the central nervous system, but they are certainly quite different in character and nature. This discussion can also be used to address some of what I think is a dearth of public understanding of the nature of the nervous system and just how difficult it can be to treat, let along cure, the diseases from which it can suffer.

A quick disclaimer at the beginning: I haven’t been closely reading the literature on either disease for quite some time, though I do notice related stories in reliable science-reporting sites, and I’ll try to do a quick review of any subjects about which I have important uncertainties. But if I’m out of date on anything specific, feel free to correct me, and try to be patient.

First a quick rundown of the two disorders.

Alzheimer’s is a degenerative disease of the structure and function of mainly the higher central nervous system. It primarily affects the nerves themselves, in contrast to neurologic diseases that interfere with supporting cells in the brain*. It is still, I believe, the number one cause of dementia** among older adults, certainly in America. It’s still unclear what the precise cause of Alzheimer’s is, but it is associated with the development of “cellular atypia made of what are called “neurofibrillary tangles” within the cell bodies of neurons, and these seem to interfere with normal cellular function. To the best of my knowledge, we do not know for certain whether the plaques are what directly and primarily cause most of the disease’s signs and symptoms, or if they are just one part of the disease. Alzheimer’s is associated with gradual and steadily worsening loss of memory and cognitive ability, potentially leading to loss of one’s ability to function and care for oneself, loss of personal identity, and even inability to recognize one’s closest loved ones. It is degenerative and progressive, and there is no known cure and there are few effective treatments that are not primarily supportive.

Parkinson’s Disease (the “formal” disease as opposed to “Parkinsonism”, which can have many causes, perhaps most notably the long-term treatment of psychiatric disorders with certain anti-psychotic medicines), is a disorder in which there is loss/destruction of cells in the substantia nigra***, a region in the “basal ganglia” in the lower part of the brain, near the takeoff point of the brainstem and spinal cord. It is dense with the bodies of dopaminergic neurons, which there seem to modulate and refine motor control of the body. The loss of these nerve cells over time is associated with gradual but progressive movement disorders, including the classic “pill-rolling” tremor, shuffling gait, blank, mask-like facial expression, and incoordination with tendency to lose one’s balance. There are more subtle and diffuse problems associated with it, including dementia and depression, and like Alzheimer’s it is generally progressive and degenerative, and there is no known “cure”, though there are treatments.

Let me take a bit of a side-track now and address something that has been a pet peeve of mine, and which contributes to a general misunderstanding of how the nervous system and neurotransmitters work, and how complex the nature and treatment of diseases of the central nervous system can be. This may end up causing this blog post to require at least two parts, but I think it’s worth the diversion.

I mentioned above that the cells of the substantia nigra are mainly dopaminergic cells. This means that they are nerve cells that transmit their “messages” to other cells mainly (or entirely) using the neurotransmitter dopamine. The term “dopaminergic” is a combination word, its root obviously enough being “dopamine” and its latter half, “ergic” relating to the Greek word “ergon” which means to do work. So “dopaminergic” means those cells do their work using dopamine, and—for instance—“serotonergic” refers to cells that do their work using serotonin. That’s simple enough.

But the general public seems to have been badly educated about what neurotransmitters are and do; what nerve impulses are and do; and what the nature of disorders, like for instance depression, that involve so-called “chemical imbalances” really entails.

I personally hate the term chemical imbalance. It seems to imply that the brain is some kind of vat of solution, perhaps undergoing some large and complex chemical reaction that acquires some mythical state of equilibrium when it’s working properly, but when, say, some particular reactant or catalyst is present in too great or too small a quantity, doesn’t function correctly. This is a thoroughly misleading notion. The brain is an incredibly complex “machine” with hundreds of billions of cells interacting in extremely complicated and sophisticated ways, not a chemical reaction with too many or too few moles on one side or another.

People have generally heard of dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and the like, and I think many people think of them as related to specific brain functions—for instance, serotonin is seen as a sort of “feel good” neurotransmitter, dopamine as a “reward” neurotransmitter, epinephrine and norepinephrine as “fight or flight” neurotransmitters, and so on.

I want to try to make it very clear: there’s nothing inherently “feel good” about serotonin, there’s nothing inherently “rewarding” about dopamine, and—even though epinephrine is a hormone as well as a neurotransmitter, and so can have more global effects—there’s nothing inherently “fight or flight” about the “catecholamines” epinephrine and norepinephrine.

All neurotransmitters—and hormones, for that matter—are just complex molecules that have particular shapes and configurations and chemical side chains that make them better or worse fits for receptors on or in certain cells of the body. The receptors are basically proteins, often combined with special types of “sugars” and “fats”. They have sites in their structures into which certain neurotransmitters will tend to bind—thus triggering the receptor to carry out some function—and to which other neurotransmitters don’t bind, though, as you may be able to guess from looking at their somewhat similar structures, there can be some overlap.

Dopamine

Serotonin

Epinephrine

Neurotransmitters are effectively rather like keys, and their functions—what they do in the nervous system—are not in any way inherent in the neurotransmitter itself, but in the types of processes that get activated when they bind to receptors.

There is nothing inherently “rewarding” about dopamine, any more than there is anything inherently “front door-ish” to the key you use to unlock the front door of your house, or “car-ish” to the keys that one uses to open and turn on cars. It’s not the key or the lock that has inherent nature, it’s whatever function is initiated when that key is put into that lock, and that function depends entirely on the nature of the target. The same key used to open your door or start your car could, in principle, be used to turn on the Christmas lights in Rockefeller Center or to launch a nuclear missile.

Dopamine is associated with areas of the nervous system that function to reward—or more precisely, to motivate—certain behaviors, but it is not special to that function. As we see in Parkinson’s Disease, it is also used in regions of the nervous system involved in modulating motor control of the body. The substantia nigra doesn’t originate the impulses for muscles to move, but it acts as a sort of damper or fine tuner on those motor impulses.

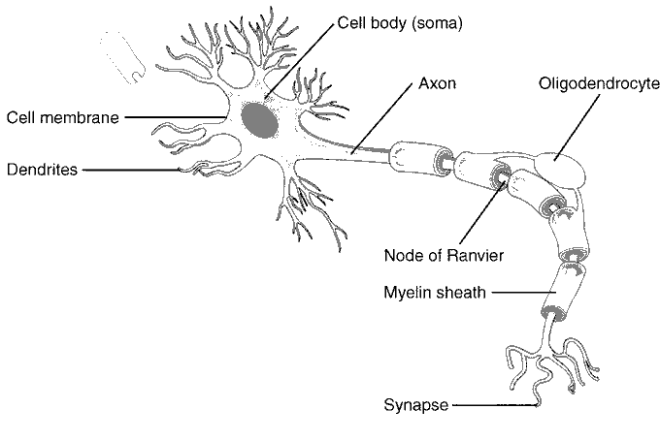

Neurotransmitters work within the nervous system by being released into very narrow and tightly closed spaces between two nerve cells (a synapse), in amounts regulated by the rate of impulses arriving at the bulb of the axon. Contrary to popular descriptions, these impulses are not literally “electrical signals” but are pulses of depolarization and repolarization of the nerve cell membrane, involving “voltage-triggered gates****” and the control of the concentration of potassium and sodium ions inside and outside the cell.

A highly stylized synapse

The receptors then either increase or decrease the activity of the receiving neuron (or other cell) depending on what their local function is. It’s possible, in principle, for any given neurotransmitter to have any given action, depending on what functions the receptors trigger in the receiving cell and what those receiving cells then do. However, there is a fairly well-conserved and demarcated association between particular neurotransmitters and general classes of functions of the nervous system, due largely to accidents of evolutionary history, so it’s understandable that people come to think of particular neurotransmitters as having that nature in and of themselves…but it is not accurate.

Okay, well, I’ve really gone off on my tangents and haven’t gotten much into the pathology, the pathophysiology, or the potential (and already existing) treatments either for Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. I apologize if it was tedious, but I think it’s best to understand things in a non-misleading way if one is to grasp why it can be so difficult to treat and/or cure disorders of the nervous system. It’s a different kind of problem from the difficulties treating cancer, but it is at least as complex.

This should come as no surprise, given that human nervous systems (well…some of them, anyway) are the most complicated things we know of in the universe. There are roughly as many nerve cells in a typical human brain as there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy, and each one connects with a thousand to ten thousand others (when everything is functioning optimally, anyway). So, the number of nerve connections in a human brain can be on the order of a hundred trillion to a quadrillion—and these are not simple switching elements, like the AND, OR, NOT, NAND, and NOR gates for bits in a digital computer, but are in many ways continuously and complexly variable even at the single synapse level.

When you have a hundred trillion to a quadrillion more or less analog switching elements, connecting cells each of which is an extraordinarily complex machine, it shouldn’t be surprising that many things can go wrong, and that figuring out what exactly is going wrong and how to fix it can be extremely difficult.

It may be (and I strongly suspect it is the case) that no functioning brain of any nature can ever be complex enough to understand itself completely, since the complexity required for such understanding increases the amount and difficulty of what needs to be understood*****. But that’s okay; it’s useful enough to understand the principles as well as we can, and many minds can work together to understand the workings of one single mind completely—though of course the conglomeration of many minds likewise will become something so complex as likely to be beyond full understanding by that conglomeration. That just means there will always be more to learn and more to know, and more reasons to try to get smarter and smarter. That’s a positive thing for those who like to learn and to understand.

Anyway, I’m going to have to continue this discussion in my next blog post, since this one is already over 2100 words long. Sorry for first the delay and then the length of this post, but I hope it will be worth your while. Have a good weekend.

*For instance, Multiple Sclerosis attacks white matter in the brain, which is mainly long tracts of myelinated axons—myelin being the cellular wraparound material that greatly speeds up transmission of impulses in nerve cells with longish axons. The destruction of myelin effectively arrests nerve transmission through those previously myelinated tracts.

**“Dementia” is not just some vague term for being “crazy” as one might think from popular use of the word. It is a technical term referring to the loss (de-) of one’s previously existing mental capacity (-mentia), particularly one’s cognitive faculties, including memory and reasoning.

***Literally, black substance.

****These are proteins similar to the receptors for neurotransmitters in a way, but triggered by local voltage gradients in the cell membrane to open or close, allowing sodium and/or potassium ions to flow into and out of the cell, thereby generating more voltage gradients that trigger more gates to open, in a wave that flows down the length of the axon, initially triggered usually at the body of the nerve cell. They are not really in any way analogous to an electric current in a wire.

*****You can call that Elessar’s Conjecture if you want (or Elessar’s Theorem if you want to get ahead of yourself), I won’t complain.