Hello and good morning. It’s Thursday again, and so it’s time for a more fully fledged blog post for the week, in the manner in which I used to write them when I was writing fiction the rest of the week (and playing some guitar in the time between writing and starting work most days).

I’ve been rather sick almost every day since last week’s post, except for Friday. I don’t think it’s a virus of any kind, though that may be incorrect. It’s mainly upper GI, and it’s taken a lot of the wind out of my sails.

I haven’t played guitar at all since last Friday. I’ve also only written new fiction on a few of the days—Friday, Monday, and Wednesday, I think—since the last major post. Still, on the days I wrote, I got a surprisingly good amount of work done, I guess. It seems as though Extra Body is taking longer than it really ought to take, but once it’s done, I’m going to try to pare it down more than I have previous works, since my stuff tends to grow so rapidly.

I’ve been trying to get into doing more studying and “stuff” to correct the fact that I didn’t realize my plans to go into Physics when I started university. I had good reasons for this non-realization, of course, the main one being the temporary cognitive impairment brought about by heart-lung bypass when I had open heart surgery when I was eighteen.

I’m pretty sure I’ve written about that before, but I didn’t know about it then, and I didn’t learn about it until I did the review paper I wrote for my fourth-year research project in medical school. I just felt discouraged and stupid, though I consoled myself by studying some truly wonderful works of literature as an English major, including once taking two Shakespeare courses at the same time. That was great!

It’s always nice to learn about things, all other things being equal. I don’t think there are pieces of true information about the world that it is better not to know. Our response to learning some intimidating truth about the greater cosmos may not be good, but the fault then lies not with the stars but with ourselves. If you truly can’t handle the truth, then the problem is with you, not with the truth.

Of course, knowing what is true is generally not simple, except about simple things, and often not even about those. This is the heart of epistemology, the philosophical branch that deals with how we know what we know when we know it, so to speak. The subject may seem dry at times, especially when it gets weighed down by jargon that serves mainly just to keep lay people from chiming in on things—at least as far as I can see—but it is important and interesting at its root.

Not but what there can’t be good reasons for creating and using specific and precise and unique terms, such as to make sure that one knows exactly what is meant and doesn’t fall into the trap of linguistic fuzziness which often leads to misunderstanding and miscommunication. That’s part of the reason most serious Physics involves mathematical formalism; one wants to deal with things precisely and algorithmically in ways that one can make testable and rigorous predictions.

Physicists will sometimes say that they can’t really convey some aspect of physics using ordinary language, that you have to use the math(s), but that can’t be true in any simplistic sense, or no one would ever be able to learn it in the first place. Even the mathematics has to be taught via language, after all. It’s just more cumbersome to try to work through the plain—or not so plain—language to get the precise and accurate concepts across.

And, of course, sometimes the person tasked with presenting an idea to someone else doesn’t really understand it in a way that would allow them to convey it in ordinary language. This is not necessarily an insult to that person. Richard Feynman apparently used to hold the opinion that if you truly understand some subject in Physics, you should be able to produce a freshman-level lecture about it that doesn’t require prior knowledge, but he admitted freely when he couldn’t do so, and was known to say that this indicated that we—or at least he—just didn’t understand the subject well enough yet.

I don’t know how I got to this point in this blog post, or indeed what point I’m trying to make, if there is any point to anything at all (I suppose a lot of that would depend on one’s point of view). I think I got into it by saying that I was trying to catch up on Physics, so I can deal with it at a full level, because there are things I want to understand and be able to contemplate rigorously.

I particularly want to try to get all the way into General Relativity (also Quantum Field Theory), and the mathematics of that is stuff that I never learned specifically, and it is intricate—matrices and tensors and non-Euclidean geometry and similar stuff. It’s all tremendously interesting, of course, but it requires effort, which requires time and energy.

And once other people have come into the office and the “music” has started, it’s very hard for me to maintain the required focus and the energy even in my down time, though I have many textbooks and pre-textbook level works available right there at my desk. I’ve started, and I’m making progress, but it is very slow because of the drains on my energy and attention.

If anyone out there wants to sponsor my search for knowledge, so I wouldn’t have to do anything but study and write, I’d welcome the patronage.

But I’m not good at self-promotion, nor at asking for help in any serious way. I tend to take the general attitude that I deserve neither health nor comfort in life, and I certainly don’t expect any of it. I’m not my own biggest fan, probably not by a long shot. In fact, it’s probably accurate to say that I am my own greatest enemy.

Unfortunately, I’m probably the only person who could reliably thwart me. I’m sure I’m not unique in this. Probably very few people have literal enemies out there in the world, but plenty of people—maybe nearly everyone—has an enemy or enemies within. This is one of the things that happens to beings without one single, solitary terminal goal or drive or utility function, but rather with numerous ones, the strengths of which vary with time and with internal and external events.

I’ve said before that I see the motivations and drives of the mind as a vector sum in very much higher-dimensional phase space, but with input vectors that vary in response to outcomes of the immediately preceding sum perhaps even more than they do with inputs from the environment. I don’t think there will ever be a strong way fully to describe the system algorithmically, though perhaps it may be modeled adequately and even reproduced. This is the nature of “Elessar’s First Conjecture”: No mind can ever be complex enough to understand itself fully and in detail*.

A combination of minds may understand it though—conceivably. Biologists have mapped the entire nervous system of C elegans, a worm with a precisely defined nervous system with an exact number of neurons, and of course, progress is constantly being made on more advanced things. But even individual neurons are not perfectly understood, even in worms, and the interactions between those nerves and the other cells of the body is a complex Rube Goldberg machine thrown together from pieces that were just laying around in the shed.

Complexity theory is still a very young science.

And the public at large spends its energy doing things like making and then countering “deep fakes” and arguing partisan politics with all the fervor that no doubt the ancient Egyptians and Greeks and Romans and the ancient Chinese and Japanese and Celts and Huns and Iroquois and Inca and Aztecs and Mayans and everyone else in ancient, vanished, or changed, civilizations did. They all surely imagined that their daily politics were supremely important, that the world, the very universe, pivoted on the specifics of their little, petty disagreements and plans and paranoias**.

And so often so many of them, especially the young “revolutionaries”, whose frontal lobes were far from fully developed, were willing to spill the blood of others (and were occasionally even willing to sacrifice themselves) in pursuit of their utopian*** imaginings. This is true from the French Revolution to the Bolsheviks to the Maoists and the Killing Fields, and before them all the way back to the Puritans of Salem, and the Inquisition, and the Athenians who executed Socrates, and the killers of Pythagoras****, and the millions of perpetrators of no-longer-known atrocities in no-longer-known cultures and civilizations.

And then, of course, we have the current gaggle of fashionably ideological, privileged youth, who decry the very things that brought them all that they take for granted, and who will follow in the blood-soaked footsteps of those I mentioned above—l’dor v’dor, ad suf kul hadoroth, a-mayn.

In the meantime, I’ll try to keep writing my stories, and try to keep learning things, and if I’m able to develop an adequate (by my standards) understanding of General Relativity and Quantum Field Theory, it’s just remotely possible that I might even make legitimate contributions to the field(s). But more likely I’ll self-destruct, literally, well before any of that happens.

I’ve probably gone on too long already, as has this blog post. I thank you for your patience with my meanderings. Please try to have a good day, and I hope those of you who celebrate it are having a good Passover.

TTFN

*This implies that Laplace’s Demon could not be within the universe about which it knows the position and momentum of every particle and the strength of every force. It needs to be instantiated elsewhere.

**Should that be “paranoiae”? It feels like that ought to be the formal way of putting it, but Word thinks it’s misspelled.

***Not to be confused with “eutopian”. Utopia means “no place”, whereas Eutopia would mean “good place” or “pleasant place” or “well place”.

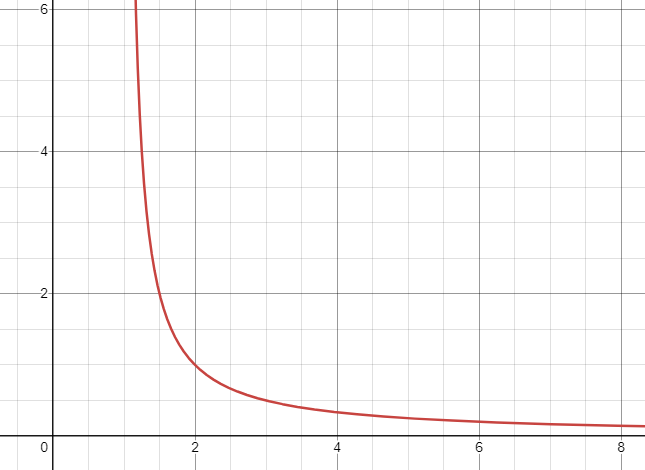

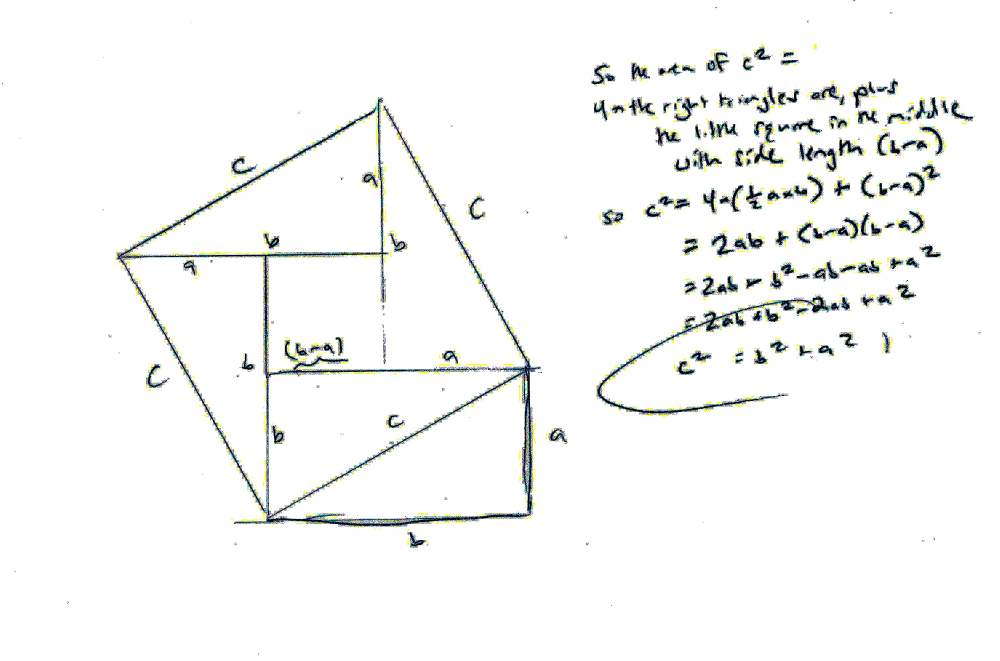

****He was caught despite a head start, so I’ve heard, because he refused to cross a bean field, believing that beans were evil. He was a weird guy. It’s apparently from his followers that the term “irrational”—which originally just meant a number that cannot be expressed as the ratio of two whole numbers—developed its connotation as “crazy” or “insane”. They didn’t like the fact that irrational numbers even existed. Too bad for them; there are vastly more irrational numbers than rational ones…an uncountable infinity versus a “countable” infinity. It’s not even close.