It’s Tuesday now, in case you didn’t know, though of course you might not be reading this on a Tuesday. If by some bizarre set of circumstances my writing is still being read in the far future‒or even more improbably that it goes backward in time somehow or tunnels across to some other part of the universe that nevertheless has people who can read English‒there may not even be Tuesdays where and when you exist.

In case that’s the case, I will just say that in the 20th and 21st centuries‒and actually for quite some time before‒we divided the days into groups of 7, which we called weeks*. There were roughly 52 of these in a year (52 x 7 = 364, one day and some change less than a full year).

In the English-speaking world we called these days Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. I could go into the etymology of those names, but that’s a bit of a pain. Anyway, you’re the ones who are in some future, presumably advanced civilization; why can’t you look that stuff up for yourselves?

Anyway, our “official work week” ran from Monday through Friday, with Saturday and Sunday off. However, that was far from the only schedule people followed, and in a form of evolution due to mutual competition, people vied with each other to work more days and longer hours for less pay, because other people were willing to do it. Not to participate would lead one to be less likely to get or keep a job, and that could lead to destitution‒at least somewhat more quickly than does steadily working longer and longer for less and less, which is a kind of creeping but pernicious societal malaise.

Of course, other, parallel forces led to decreasing regulation of companies’ ability to “encourage” their workers to work more for less, and since in the short term** everyone works in response to their local incentives, people tended to allow these things to happen. And lawmakers and regulators, subject to the inherently woefully dysfunctional political party system, became less and less incentivized to care about the needs and worries of those they nominally represented, and to whom they had sworn their service***.

They were happy to allow the fortunate wealthy and powerful to take advantage of the foolishly earnest and mutually (and self-destructively) competitive citizens, because they were rewarded for allowing it.

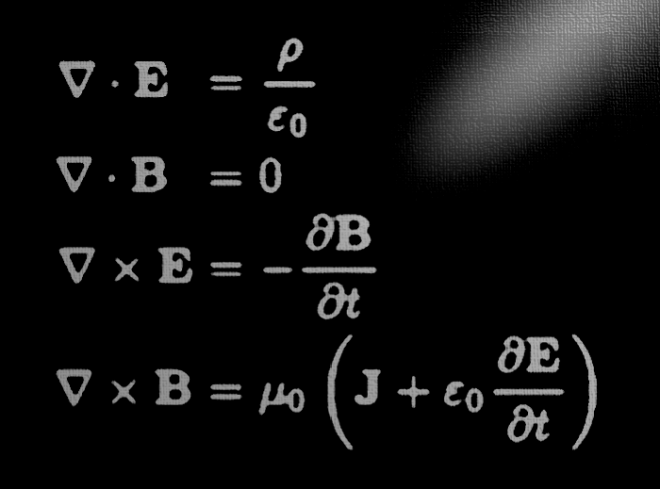

Everyone responds to local forces, of course. Even spacetime itself responds to the spacetime immediately adjacent to it, as the electromagnetic field responds to the state of the field immediately adjacent to it, as demonstrated by the implications of Maxwell’s famous equations, which I’m sure jump right out at you:

Of course, the meaning of “local” is circular here, almost tautological, since the definition of local is merely “something that can affect another thing directly” more or less.

So it’s only too possible for a system to evolve itself into a state that is overall detrimental to those within the system. Everyone, even the most seemingly successful, can be in a worse situation than they would be in otherwise, but it’s very difficult to see the way out, to get a “bird’s eye view” of the landscape, if you will.

One can therefore get stuck in situations where, despite the overall equilibrium being detrimental to everyone, any one individual taking action to try to move things in a better direction would make their local situation worse for them.

How is one to respond to such a situation? Well, one can simply go along with it and try to do what’s best for oneself locally, and that is what most people do most of the time‒understandably enough, even though the overall situation may be evolving toward its own miserable destruction.

Or, of course, one could do what family therapists are often said to do: effectively setting off a bomb***** in the middle of a difficult situation and seeing what happens when the dust settles, figuring that nothing is likely to be much worse than things are at a given present. At least this allows for a new system to form, like the biosphere after the various mass extinctions. Maybe it will become better than the previous one.

Maybe they all will always evolve toward catastrophe, to collapse and then be replaced by a new system.

It would be better if people could learn, and could deliberately change local incentives in careful and measured ways, adjusting settings to correct for and steer things away from poorer outcomes and so on, in ways that are not too disruptive at any given place or time. That’s nominally what many of our systems are meant to be doing, but they don’t do a very good job at it.

Probably it would be better to do a hard reset. But I’m not sure. And it’s probably not worth the effort. The odds of humanity surviving to become cosmically significant seem very low to me, and I’m not sure it would be good for the universe‒whatever that might mean‒if they do.

It’s probably all pointless, and I’m tired of it, anyway. I don’t want to be part of this equilibrium or lack thereof anymore. I want to make my own quietus. Maybe “civilization” should do the same.

*Not to be confused with “weak”, which sounds the same but means more or less “the opposite of strong” and has little or nothing to do with divisions of time.

**And that’s pretty much the only term that comes naturally and easily to humans, for sound biological but horrible psychological and sociological reasons.

***If they were Klingons, they would surely be slain for their dishonor. I don’t necessarily disagree with such an outcome morally, but practically, it would probably lead to increasing chaos****, so we understandably avoid it most of the time.

****It’s an open question whether such chaos is inherently bad.

*****Metaphorically, of course. At least, it’s usually metaphorical.

Of course Maxwell’s equations pop right out at me! I have them tattooed on the back of my hand. 🙂

That’s an awesome thought. ^_^ I wonder if anyone has tried to tattoo the whole standard model of particle physics Lagrangian onto…any part of their body.

Just hope that it’s correct and doesn’t need to be revised afterward.

Ouch!!