It’s Tuesday morning, and I’m not writing any fiction today, because I don’t feel terribly well. I took a lot of pain medicine yesterday, of more than one kind, and I think it upset my stomach.

Indeed, I woke up very early this morning feeling nauseated. I wasn’t queasy enough to throw up, which is in some ways disappointing, since that always brings at least a bit of relief, but I was certainly unable to rest. I decided, finally, just to get up and get an Uber in to the office, since I knew if I waited too long I might choose to stay “home” for the day, and that wouldn’t make me feel any better.

So I showered and then ordered an Uber; today the prices were reasonable, even for a ride all the way in to the office, which helped cement my decision. It’s frivolous, of course, in that it’s an unnecessary expense, and I really need to avoid doing it too often. But it ended up being interesting.

I decided, while en route, not to do any writing in the car, either on my phone or on my laptop computer, since I was worried about car-sickness. Instead, I eventually started playing with the notion of the standard Uber tip buttons. I thought, to myself, if I were to give a 25% tip (the maximum automatic one), that fact would increase the total amount paid, and so the net tip would be less than 25% of the new total. So, if I added 25% of the extra, that would increase the total even more, but it would then still be less than 25% of the new total, so I would need to add more, and eventually it would converge on a final number. As I did a quick bit of figuring, I realized that the final amount I was approaching was 33% more than the original amount.

I realized—this is not a terribly impressive mathematical insight, I know, but I was and am queasy and so it was an interesting distraction—that this process effectively entailed an infinite series, in the form of 1 + 1/n + 1/n2 + 1/n3 +… and so on. The first little ad hoc trial I had done made me realize that, at least that series had taken n as 4, and iterated it, giving a final number that was 1 and 1/3. That seemed interesting.

I wondered if this was a general pattern. So, using a calculator this time, I took one then added a fifth, then added 1 over 5 squared, then one of 5 cubed and so on, and pretty clearly arrived at a final total that was one and a quarter. A few other numbers made it clear that this was general, and it makes sense if you work it backwards. 25 (one quarter) added to 100 gives you 125, and 25 out of 125 is always going to be on fifth of the new total , or 20%. 33 and a third (or a third) added to 100 gives you 133 and a third, and 33 and a third out of 133 and a third will always be a quarter of the total.

And then, of course, there’s the old mathematics joke about an infinite number of mathematicians going into a bar, with the first one ordering a pint of beer, the second ordering a half pint, the third ordering half as much as the second, the fourth ordering half as much as the third and so on, until finally the bartender holds up a hand and says, “Gentlemen! Know your limits!” before drawing two pints of beer and putting them out on the table. This is because 1 + ½ + ¼ + … goes to 2 in the limit as iterations go to infinity.

So, the series 1 + 1/n + 1/n2 + 1/n3 +…converges to 1 + 1/(n-1), which is (n-1)/(n-1) + 1/(n-1), which is n-1+1/(n-1) or just n/(n-1). I’ve tried to start working the algebra of the infinite series to produce this result (just for fun), but didn’t put much time into it, and it’s not really necessary, since I can see the result clearly by working backwards.

Of course, looking at my result, I know this is really basic stuff, and at some level I already “knew” it, at least formally. But there’s nothing like working out a thing for yourself to make it sink in and make true sense to you.

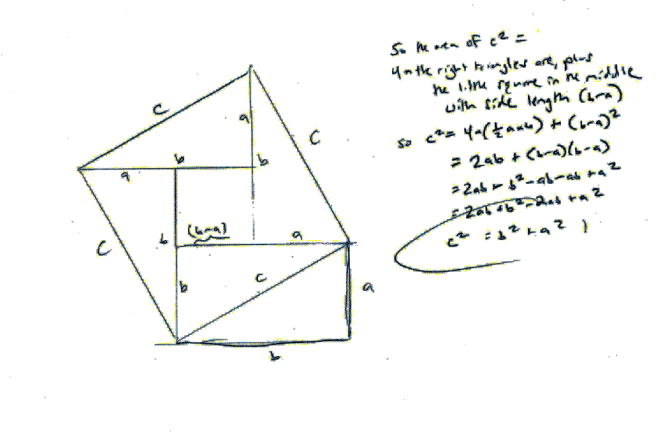

This is a bit like something I did when I was in the Education Department at FSP West during my involuntary vacation with the Florida DOC. I was helping inmates try to get their GEDs, which was rewarding work given the circumstances. But at one point it occurred to me that I didn’t think I’d ever seen the Pythagorean Theorem proven*. So, I set out to prove it for myself, just for a laugh. It looked something like this:

I didn’t use any of the standard, purely geometrical proofs that one often sees, but instead applied a combination of geometry and algebra that I kind of fiddled together on the spot. I don’t know if what I did was perfectly rigorous; probably not. Nevertheless, after I’d worked things through and simplified my algebra and indeed came out with c2 = b2 + a2, I was more convinced than ever before that the Pythagorean Theorem was not merely a well-supported hypothesis, but was indeed a theorem, and that given Euclidean geometry and so on, it was absolutely true.

All this is frivolous, or trivial, or whatever the term you might want to apply. It certainly has little bearing on my day to day life. But it is reassuring to think that, contrary to popular belief, it is possible to have new insights into fundamental ideas and things, however basic they might be, even at an older age (in my forties and fifties in these cases). The human brain does not stop “growing” or improving after one reaches one’s twenties or thirties or after one has left one’s teens (or at least, whatever kind of brain I have doesn’t stop). Even old dogs can be taught new tricks; and how much more amenable to teaching are naked house apes!

I’ve often been frustrated when people complain that they learned things like the Pythagorean Theorem in high school (or whenever) and had never had to use them at any point in their lives. That may well be true in a simple sense, though I think the usefulness of that theorem might surprise people (it appears often in the workings of advanced physics, for instance, including in the Lorentz transformations in Special Relativity, and also in calculating the probabilities of outcomes from the magnitudes of the wave equation when makings measurements of a quantum system).

But ultimately, I feel like asking such complainers, “Do you do push-ups in order to become better at doing push-ups? Do you do bench presses and squats to become competitive squatters and pressers of benches? Do you jog to become professional joggers? Do you do yoga to become a champion yogi? No, the vast majority of people who do such things do them to make themselves fitter overall, stronger, with better endurance and flexibility, to be better able to do the many things in the world for which it will be an advantage for them to improve their strength and their flexibility and their endurance, and to be healthier overall!”

So it is with exercise of the mind, except the mind is far more plastic, far more able to be improved and trained, than the structures and strengths of the muscles and bones and ligaments and cardiovascular system. Learning some of the methods of geometry and algebra and calculus, learning basic physics, including Newtonian physics and thermodynamics, learning some Boolean logic, some probability and statistics, some basic biology and chemistry…all these things are both inherently useful, and also give you skills and tools and abilities that are adaptable to hitherto unguessed situations and problems in the world, and give you insight into how much commonality there is to the structure of reality.

Understanding a bit about Chaos and Complexity theory can help you recognize why the specifics of the weather are fundamentally unpredictable but nevertheless the climate can be amendable to explanation and broad prediction. Understanding a bit about Bayesian reasoning can give you the comfort of knowing that, even if you have a positive mammogram, and that test has an 80% sensitivity, you probably have nothing like an 80% chance of having cancer. Indeed, you could be an order of magnitude or so less likely than that, depending on base rates and false positive rates and the like.

And in a somewhat orthogonal area of inquiry, if you want to understand something about the human condition, it wouldn’t hurt to expose yourself to the works of Shakespeare, who wrote about that subject as well as or better than practically anyone else ever has, and who did it in remarkable and beautiful language, coining figures of speech we in the “Anglosphere” still use, regularly, in daily life, four hundred years after he created them.

Also, if you live your whole life without ever having read book one of Paradise Lost, I think you will have sadly missed out on a great experience. It’s not really a very long read. Milton made his Satan a relatable and charismatic, almost heroic, character, and seeing how he did this can help you understand the power and persuasion demagogues and ideologues can bring to bear in the world, and how dangerous and yet enticing they can be. Also, Milton’s writing is just beautiful, sometimes better even than Shakespeare.

And in To His Coy Mistress, Andrew Marvell prefigures the works of Billy Joel’s Only the Good Die Young by over 300 years. And I’m pretty sure Pink Floyd referenced the work in Time.

Anyway, that’s what I did this morning to distract myself from an upset stomach, showing that these pursuits and skills can have wildly unpredictable uses. So, until and unless you have actual organic illness that prevents your brain from learning, you can still grow, and can take more and more of the universe into your mind. And, as Milton’s big bad himself said, “What is else not to be overcome?”

*It probably was at some point in my education, but I didn’t recall the proof, so it had clearly never really sunk in for me. I didn’t doubt the theorem—all the greatest mathematical minds of antiquity and modernity were convinced of it, and it has always worked in practice. But that’s not quite the same thing.